Podcast Description

About three years ago, many of my friends moved away within a six month period.

While I was excited for these friends, I also grieved; my friends are my main support system, my family. How would I keep these friendships alive? I invested a lot of energy into thinking about it, through which I developed what I’m tentatively calling the “Your People” framework.

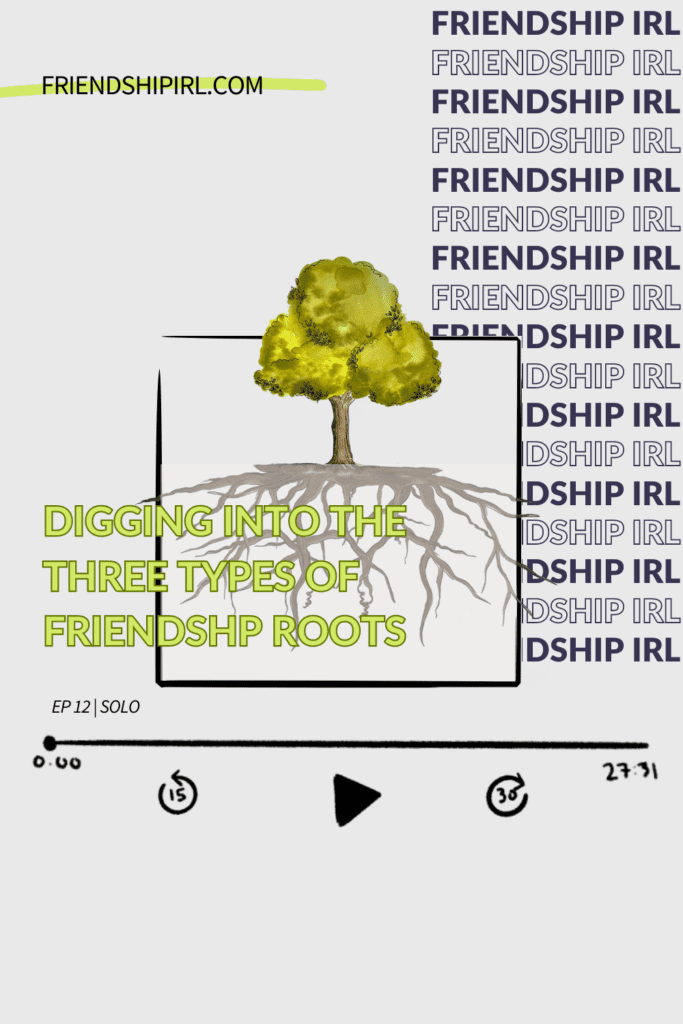

The best way to think about this framework is to imagine a tree. Trees start as seeds, and then you provide them with nutrients and soil. Over time, trees grow roots. Some roots get really thick and strong; some grow deep. Some grow offshoots. The more roots that grow, the more stable the tree.

In my friendship theory, there are three kinds of roots, which I’ll dig into today. My hope is that this framework and language helps people think about these relationships and consider what actions to take to build better versions of our friendships.

Want more information? Visit my website!

In this episode you’ll hear about:

- SHARED EXPERIENCE ROOTS and their offshoot roots – i.e., when you’re doing something related to the shared experience root, but in a way you’re comfortable

- EMOTIONAL INTIMACY ROOTS – what we know about our friends and our shared memories – plus shared/overlapping history roots and big/small intimacies

- STORY ROOTS – the beliefs you have about your friendships, and how we come to develop those beliefs

- How letting roots (i.e., friendships) die is not a bad thing – we can’t be in high school geometry class forever – but it doesn’t mean it’s not a sad thing

- How to keep these friendships thriving as we grow and change, and how to replace dead story root with simpler, more straightforward story roots

- One of the biggest problems when it comes to adult friendships – plus, the REAL foundations of these friendships

Reflection Question:

What are your most common friendship roots – shared experience roots, emotional intimacy roots, or story roots?

Notable Quotes from Alex:

“Trees start out as seeds. There really aren’t any roots. But you put that seed in the soil, and you provide it with some nutrients, soil itself, time, water, fertilizer, and it slowly starts to grow roots. They’re not very strong roots to start with. There aren’t very many roots, they don’t go very deep. They start very dainty, delicate, finicky. You have to pay a lot of attention to keep that tree growing. But over time with more nutrients, they grow more roots. Some of those roots get really thick and strong. Some grow really deep. Some grow offshoots. The more roots you grow, the more stable that tree is in the ground. ”

“It’s just so heartwarming that my obsessive thinking about this for a couple of years is creating some language we can use to start to think about how these relationships are actually working in our life and what’s holding them together. And, also, for us to look at our friendships and consider what actions we might take to reinvest in a friendship, to build a better version, or to work through a problem, so that we can all start to become our own master gardeners.”

Resources & Links

Like what you hear? Visit my website, leave me a voicemail, and follow me on Instagram!

Want to take this conversation a step further? Send this episode to a friend. Tell them you found it interesting and use what we just talked about as a conversation starter the next time you and your friend hang out!

Leave Alex a voicemail!

Can I add you to the group chat?

Don't miss an update - Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Until next time…

Take the conversation beyond the new podcast on friendship! Follow Alex on Instagram (@itsalexalexander) or Tiktok (@itsalexalexander), or send her a voice message directly with all your friendship thoughts, problems, and triumphs by heading to AlexAlex.chat and hitting record.

Episode Transcript

Podcast Intro 00:02

Alrighty, gang. Here’s to nights that turn into mornings and friends that turn in family. Cheers!

Podcast Intro 00:18

Hello, Hello, and welcome to the Friendship IRL podcast. I’m your host, Alex Alexander. My friends… They would tell you; I like to ask the hard questions. You know who I am in the group? I’m the person that’s saying, “Okay, I’m going to ask this question, but don’t feel like you have to answer it.” And now, I can be that friend for you, too.

Alex Alexander 00:50

Yesterday, I was responding to some Instagram comments. And there was a comment or post that I’d made about consistency and your friendships. And I’m assuming that the person who commented, it just appeared on… on their feed, they don’t follow me. But they responded and said, “Showing up for your friends doesn’t necessarily mean calling them every day.” You are totally right. Sure, it doesn’t. But unfortunately, Instagram is just a bunch of bite sized pieces of content. And that is a problem I constantly have. This is not a concept, friendship and community that is, that has much language, any terms. Most people haven’t spent much time thinking about it. And therefore, when I post these bite sized pieces of content, people don’t have all the backstory and the context, they get confused so easily, rightfully so.

READ MORE: “ISO: Language to Describe Friendship” where I talk about one of the reasons friendship is so hard is we don’t have ways to communicate about these vital relationships.

Alex Alexander 01:53

Now, the podcast has really helped me. But sometimes I feel like I’m continuing to do that to you here to just inundate you with bite size pieces of content. Especially when I do episodes with guests where I do the narration and I pop in, those are still only one to four minute segments on a concept. I never intended to record this long string of solo episodes that I’ve been on. But I do think that there are some foundational concepts we just need to lay down. We need to record for everybody who’s consistently listening to the podcast. It’s going to be way easier for you to understand what the heck I’m talking about if I just dive into the concept as a whole, instead of continuing to piecemeal together these theories and frameworks.

Alex Alexander 03:00

Now, currently, these frameworks are new to everyone. They are frameworks that I came up with myself. And I’m not saying that they’re right, I’m just basically offering a theory out to the world. And hoping that enough people think about these topics, that 10 years from now, there’s a better version. Because we’ve cumulatively, collectively worked on these frameworks. That is my greatest hope. I just want to start the conversation. So today, I want to talk about my roots* framework. And maybe I should tell you how I came up with this. About three years ago, a very large number of friends moved away in a very short period of time, I would say about 10 Friends, that all lived very close to us moved away within a six month period. And that is a lot. It’s a lot of change. Things felt very different. I’ve talked about this before, but to me, my friendships are my main support system. So, I think that a good comparison for most people would be if you are from a larger family. Let’s say you all live within a 10 minute drive of each other. And within a six month period, five of your siblings and their significant others told you they were moving across the country. That is where I was.

Alex Alexander 04:39

There were many nights where I cried myself to sleep, mornings where I had to wake up and talk myself down. I have voice recordings, me trying to process my feelings. I was so excited for my friends to go on this path that they felt was right for them. But simultaneously, I was grieving. A whole lot of things had changed. And since my friendships are my main support system, my biggest concern was, how do I keep these friendships alive? How are we still connected? Because there is no denying the fact that we are disconnecting in certain ways as my friends moved away. That’s why I felt the grief, I had to let go of certain parts of our friendship. But what was still there? And what was the new version of this friendship going to look like? Some people, this question might be like, oh, that’s nice. Is this really a top priority? And to me, yes. I needed to figure this out. I was willing to invest a lot of time and energy to try and understand how these relationships worked in my life and how I could keep them alive.

Alex Alexander 06:04

So I started doing this work by developing the types of people framework, which I still don’t have an official name for. The top contender at the moment is the ‘Your people’ framework. That’s probably what it’s going to be. But that’s where I started. I started looking at my friendships and trying to understand kind of where they sat and what happened when somebody who was, what I now call a present friend, who you spend all this time with in your everyday life moved away. Did that make it a lesser friendship? How were you still connected? What were the ways to still feel close? What was the new peak version of this friendship? And I will never forget, I was on a podcast called Beyond the B.S. Podcast. And I don’t think they’re still recording, but the episode is still live. I actually listened to some parts of that episode this morning. And on the episode, I was talking about ways you’re connected with friends, one of the gals said, “This kind of sounds like roots.” I cannot express to you what a lightbulb moment that was for me. My brain exploded.

PODCAST EPISODE! Listen to me on Beyond the B.S. Podcast. Listen here.

Alex Alexander 07:25

Because I think that a tree is a great metaphor, and a great visual for us all to think about our friendships. And after that, I spent the better part of two years obsessively thinking about this. Changing it, modifying it, trying to find holes in my theories, trying to find things that didn’t apply. And the tree, the roots theory, it’s still here. So the rest of the episode today, I’m going to kind of walk you through this metaphor of the tree overall. And then I’m going to break down each type of route. Now, I have hundreds of pages of writing on this topic, there’s no way I’m going to cover absolutely everything in this one episode. And I don’t intend to make this a series right away. I’m sure I will record more episodes on this framework over time. But my hope is that by giving you this foundation today, when I do pop in with narration and future episodes, or I mentioned these terms, you have some foundational idea of what the heck I’m talking about.

Alex Alexander 08:41

So let’s talk about the roots. And this idea of our friendships being a tree, I think a tree is a great metaphor, because trees start out as seeds. There really aren’t any roots. But you put that seed in the soil, and you provide it with some nutrients, soil itself, time, water, fertilizer, and it slowly starts to grow roots. And they’re not very strong roots to start with. There aren’t very many roots, they don’t go very deep. They start very dainty, delicate, finicky, you have to pay a lot of attention to keep that tree growing. But over time with more nutrients, they grow more roots. Some of those roots get really thick and strong. Some grow really deep. Some grow off shoots. And the more roots you grow, the more stable that tree is in the ground. And even though it’s growing and getting bigger, we don’t really know what’s happening under the soil. Now, a master gardener might be able to look at a tree and see that the leaves are yellowing, and say to you, “You’re over watering it, or the roots are root bound.” Like they have some sense of probably what is happening, the average person looks at the yellow leaves on a tree, and just thinks something’s wrong. And then they’re gonna try a bunch of things.

READ MORE about making friends here – Roots 101

Alex Alexander 10:37

They’re going to try and be better about consistently watering, they’re going to try and water more, they’re going to try and water less, they’re going to add some more soil, maybe report it, try some fertilizer, they’re just going to try anything they can think of. And that is what I think the majority of people are doing when it comes to their friendships. Now, the other interesting thing is, even if we get the tree back, it’s going great. It’s looking good. The roots are constantly changing under the tree. So it could be the best, most beautiful version of that tree you’ve ever seen. And even when that happens below the soil, certain roots are withering and dying. They’re growing new roots in their place, some roots are getting stronger, some are impeded by maybe the pot. And they stop growing and they die. The roots are constantly changing.

Alex Alexander 11:40

So today, I want to talk about three kinds of roots. And they have some subtypes in there. Because if you can start to see these roots in your friendships, I think we can all become more of that master gardener, we can start to see how real life things are happening in our friendships, and how we might act in intentional ways to impact the roots and strengthen the tree, which is our friendship. Let me tell you the… the names of the three kinds, and they build on each other. You’re gonna see that as I talk through them. So the first one is what I call shared experience roots. The next are emotional intimacy roots. And the final kind are story roots. And there are subtypes or parts underneath those. But we’ll talk through those as we go through each kind. Now, I’ve told you all about the tree, I want to give you kind of like a real life example of when a friendship is that seed that has no roots. And that’s going to help you see how we build those initial roots with somebody. Because for a lot of people, it’s been a long time since you’ve made those initial roots with a friend, as adults, kind of collect our people quite often. And then we get out of practice of going through this initial roots stage.

Alex Alexander 13:13

So some of your closest people, we think way back, at a certain point, they were just another person in the room. I’ve talked about this before. So let’s pretend for this example, that this person… you’re in high school are all in high school, you’re sitting in geometry class. And there’s a person sitting in the desk in front of you. That’s all they are, they are the person sitting in the desk in front of you. You don’t really know anything else about them. Maybe you’ve never even seen them before at school. So what are your shared experiences? Well, you’re both in geometry, you both go to the same school. We don’t know much else about that. But we can use that. One day, you might tap on their shoulder and ask them if they did the homework. You might ask them if they like this teacher, they’re going to take this teacher’s class again next semester, you go to the same school. So, you could ask them if they’re going to make it to the assembly this afternoon. These are easy, comfortable ways to start a conversation with this person that you don’t really know anything about. And if you left geometry class and you went to lunch, and they walked by you, now they’re the person who sits in front of you in geometry. That’s who they are. And you have a shared experience. You could walk up to them and you could ask them, “Hey, did you do the homework?” It’s as simple as that.

Alex Alexander 14:40

Now, one day, maybe while you’re sitting in geometry class, this person in front of you turns around and mentions that they didn’t get the homework done last night. They were just way too nervous about soccer tryouts today. And you’re shocked. You can’t believe it. because hold on. Stick with me here. You are trying out for soccer today too. You’re both trying to have the soccer team, you’re both interested in soccer. You just found another shared interest/experience. So let’s say you will try out, you will make the team. Now you spend every day after school together at soccer practice. And one day, you might say, “Hey, we have that geometry test on Friday. Do you want to study before practice tomorrow?” And you have now taken this shared experience of geometry class and soccer. You kind of linked them together and you’re building what I call an offshoot root, which is, do you want to study together?

Alex Alexander 15:46

You know, maybe you go to the library for that one hour between practice and class. Another offshoot root for soccer might be you asking your friend, “Hey, my parents are driving me to that away game this weekend. Do you want to ride with us?” And this is slightly like a new way to spend time together. But it’s still connected to soccer. It feels less risky. Because you already know this person is going to need to go to soccer the soccer game. Versus if you said, “Hey, do you want to go to a movie on Friday?” You don’t know if they like movies, you don’t know what they’re doing on Friday, that’s less risky. That would be creating an entirely new shared experience roots. The offshoots or when you’re just doing something slightly different, but related to a way you’re already comfortable connecting.

Alex Alexander 16:37

And you slowly build up these shared experience roots over time by spending time together, and talking to our friends observing our friends. We realize we have a lot in common like the same TV shows. We only live one neighborhood away. And you just like figure these things out because you’re spending time together, doing life, connecting about things. If you follow me on social media, I talk a lot about finding ways to actually spend time with friends and do things with them. That’s because I think that shared experience roots are one of our biggest problems when it comes to adult friendships. As I talk more about the next two types of roots, you’ll see that these shared experience roots are the foundation of our friendships, in my opinion. Spending time together, or connecting about something we share in common, like share common interest in is what allows us to create all the other roots. Therefore, they’re very important.

Alex Alexander 17:50

The next type of root are emotional intimacy roots. Emotional intimacy roots are the information that we know about our friends. So when you just met this person in geometry class, you didn’t know much about them. You didn’t have any memories together, you didn’t know what their favorite things are. But over time, spending time together, you collected information about each other. Now I say the word collected, because in order to collect something, you have to see it, you have to pay attention to it. And I think that’s a very key thing to note here that we have to notice. We have to be present when we’re spending time with our friends are talking to them and paying attention to collect the emotional intimacy roots. So there’s a few subtypes of emotional intimacy roots. The first ones are the small details that we notice about each other. Their preferences, their boundaries, their perspectives. So maybe one day in geometry class, you notice that your friend brought a box of doughnuts to class. They like doughnuts. When they go to pass out the doughnuts, they’ve sneakily kept one for themselves, and it’s the chocolate one. They sit in front of you and you’re like, “Oh, is that your favorite?” And they say, “Yes.”

PODCAST EPISODE! Your Friendships are as Important as Your Romantic Relationships. Listen here!

Alex Alexander 19:16

And now you know this friend loves doughnuts and their favorite doughnut are chocolate donuts. And you file that information away for later. And as you spend time together, you start to notice your friend’s boundaries. Like when you ask them to study for the geometry test, they tell you, “Sure, but can we do it a few days before that last night? Before the test I really just like to study by myself.” And now you know. But you have to pay attention and collect that information. Another subtype of emotional intimacy roots are the memories you make. So when you are at soccer practice, you’re there. You’re in the moment. But when you leave, you still have the memory. And that memory could matter, could connect you a few hours later, a few days later, a few years later, a couple decades later. So in soccer, if you went to the state tournament, and you remember that buzzer beater winning goal, then a few hours after the game, you might say, “Do you remember when you won us the game tonight?”

Alex Alexander 20:37

And the next day, you might retell the story. And a few decades later, if you’re still friends, you might both feel transported back to that exact moment where you were 17. Nobody else in the room knows what you’re talking about. I mean, they hear the story, but it’s different. We all know it is to feel that form of intimacy of like we were there two decades ago. You can picture it the way you looked the way you felt, jumping up and down to celebrate. It’s like when you tell that story in the room, like a memory. And it was so funny. But it falls flat on anyone that wasn’t there. We’ve all had that happen. That’s what I’m talking about here. It just hits different when you’re actually there together.

Alex Alexander 21:29

And the next subtype of emotional intimacy roots are what I call shared/overlapping history. So for the purpose of this example, let’s pretend that you went over to your friend’s house, and there was a plaque on the wall and you realize that your parents and your friend’s parents went to the same college. And now you can say, “Oh, do you guys go to the football games too? Were your parents in any clubs? Where did they live on campus? Do they have any yearbooks?” There’s just certain things that you understand even though you weren’t there because of the shared or overlapping history. And the final type of emotional intimacy roots are what I call big and small intimacies. These are the conversations, requests, actions, things that we trust our friends with. And although this technically could be one category, I split it into two because I feel like everybody is looking for big intimacies. We’re looking for the things that our friends tell us, or let us in. We just feel like they’re not really letting anyone else in. The ways that we’re holding space for them or keeping their competence. Places where they’re taking little risk and being vulnerable, putting themselves out there. And we feel like that makes us a special person to them.

Alex Alexander 22:59

I think that big intimacy has become a marker, quite often of how we judge our friendships. And I don’t necessarily think that’s a good thing. Because we are missing out on all of these small ways that people are trying to let us in. And we’re just ignoring them, or maybe not giving them as much weight. Because we’re looking for the bigger, better, riskier, more vulnerable, worse, special type intimacies. So, in the purpose of this example, a big intimacy might be your friend admitting to you that they think their parents are getting divorced. But they’re probably also endless, small intimacies happening is, especially in those younger friendships. I actually think that there’s so many small intimacies in those high school college friendships. That’s one of the reasons why they’re so great, is because we’re just letting people into our lives. You know, when you’re in high school and college, you’re used to messing up, you’re used to trying things and getting them wrong. Maybe even getting in trouble from your parents, with your friends around.

Alex Alexander 24:13

Think about that as an adult. All your friends got to watch when you got feedback at work, would be so uncomfortable now, but well, that used to happen to us all the time. Now, that’s even kind of a bigger small intimacy. You know, they’re just these really subtle ways we can let people in. We can invite someone to come over in our house, we can offer someone a ride in our car. We can introduce friends. Friends, vocalize that we really enjoyed spending time with someone, be upfront and say, “Hey, this was great that we got to hang out outside of work. Can we do this more often?” Like that’s a little risky. It’s a little out there. But it’s not that out there. We’re not putting ourselves completely on the limb, but we are trying to let people in. So the thing about emotional intimacy roots. And to remind you of the types one more time, we have the small details, we learn about each other, overlapping shared history, memories, and big and small intimacies. The thing about all of these is they’re all based in the past.

Alex Alexander 25:27

At one point, we were present with our friends, and our shared experience roots.Shared Experience Roots And we paid attention, and we collected these emotional intimacy roots, and we filed them away for later. We felt like, we knew our friends better, we felt more connected. And we used our emotional intimacy roots when we were hanging out together. If we were with our friends for their birthday, we’d bring chocolate doughnuts, because we know that’s their favorite. So these are really important to know about for the final type of root, which is story roots. So your story roots are the beliefs that you have about your friendship. Some examples might be my friend cares about me, my friend supports my goals. They’re my best friend. Just kind of like generic statements we throw around when it comes to our friendships.

Alex Alexander 26:32

But really deep down, that little phrase is very emotionally charged. That belief about our friendship, sets up our expectations of the friendship. I’m gonna say that one more time. Our story roots are beliefs, and our beliefs set our expectations. And we are looking at the ways our friends act and the things they say to find evidence that supports our expectations, and therefore our beliefs. Are you ready? Okay. So there are three ways to collect story roots. The first one is that patterns of evidence create our beliefs. So you spend time with your friends, shared experience roots. And when you’re together, they act in ways that make you feel connected to each other. This normally requires them to have emotional intimacy roots to use to inform the way they act. And if you notice their actions supporting your expectations, that is evidence that supports your belief. This is why I can’t say all this in one minute sound bites. Stick with me here.

Alex Alexander 27:59

I know. I know. So the second way that we create story roots is we just choose to believe a belief, even if there’s no pattern of evidence. So if you met a new friend, and you hung out with them twice, and you just left and you’re like they’re my new best friend. And you’re serious. So it wasn’t a joke, you were serious. Or maybe you were hopeful, that might be a better way to put it. Right? You’re hopeful. But you don’t really have any evidence to back this up… this belief. But you’re sure looking for evidence, because you want to find it to support this belief you’ve just chosen. But because you don’t have a big pattern of evidence, you don’t have much evidence at all. If they do anything that doesn’t support your belief, or in fact contradicts your belief, that’s like one piece of evidence out of three total, you’re going to start questioning your belief and you’re going to feel hurt.

Alex Alexander 29:12

So sometimes, I think that just choosing a belief can lead to a fast friendship, if you and that person are acting in ways that support your belief. But this route can also lead to a massive crash and burn. So much disappointment, so many problems. Because you just don’t understand why this new best friend isn’t acting in ways that a best friend would act. Now, I’m not saying don’t do it. I’m just saying that if you do and there’s a problem, up until now, you probably haven’t had language to understand it. And hopefully, now you do. The third way we create story roots is somebody telling us that this story root exists. And quite often that somebody is society. Now, it can be a person. But there are story roots that exists out there. But we’ve just been told we should believe whether or not the actions support it. And for many people, the actions do support it and everything’s fine. But for other people, actions don’t support the story roots. And then they’re highly disappointed and confused, because they’ve been told that this is a universal truth, and they should believe it.

Alex Alexander 30:41

So an example of this would be you and a cousin are born around the same time. And growing up, you are told over and over and over again, that having cousins means that you are best friends for life. Family members are telling you this, parents are telling you this, maybe you’re even telling each other this when you start getting old enough to talk. And a lot of society supports this. Family is everything. And for a lot of people, this might work out. Actions might support this belief. And it might be great. But if you grow up and you are investing so much energy, you’re always showing up for your cousin, you’re going out of your way to drop everything and be there for them. Maybe you’re flying across the country, you’re celebrating big. But you do not feel like your cousin is acting the same way. There really is not any evidence to support this belief that you have. And it can be incredibly frustrating. It can be like, why do I even believe this. And because I believe it, I’m investing so much energy. And I don’t feel the same. I don’t feel like my cousin is my best friend. This is not what this should feel like. Their actions do not meet expectations.

Alex Alexander 32:08

If instead, we went back to the first one where patterns create evidence. And nobody ever told you that your cousin was your best friend, then you likely would have acted in ways that supported this relationship with your cousin. Had they not reciprocated, you probably would have lowered your expectations and found a new star route. Maybe something like my cousin and I have a lot of fun when we’re together. And that can be a beautiful story route, but it’s a lot less pressure on this relationship. If this had been a mutual to a relationship, then all your life, you would have seen a pattern of evidence of your cousin also going out of their way to celebrate you, support you, check in on you connect with you, find new ways to spend time together. And you would have done the same. And you would have had so much evidence that you grew up and you believed my cousin’s always hear from me. Whether or not that is true for anybody else, it is true for you. You have the evidence and the pattern that it is true.

Alex Alexander 33:23

And the interesting thing about this evidence in this pattern is that, like I said before, it all builds on itself. So your whole life, you’ve spent time together, shared experience roots. So that might be family gatherings. But you also travel together. You spend holidays together. You talk about your mutual level books. And while you’re doing all that you’re collecting information about each other, you’re learning about each other. You’re making memories together. And then you’re spending time together like on that trip where your cousin brings your favorite snacks. And they say things to you like, “Hey, I know that every few days you need a day alone. So I planned to go off and do something by myself today.” And even if on this trip, one of the days your cousin did something that just did not feel very… well, they… when they acted in a way that contradicted a belief you have. If you believe, you know, they really support me. And you told them you think you’re up for a promotion and they acted not so supportive at first, you have so much evidence that although it doesn’t feel great to have something contradict your belief, you’re like, oh, well, today must just be a day. They’re having a day. And it doesn’t really affect your story root that much because you have so much… much consistent evidence to support your belief that it’s not that big of a deal.

Alex Alexander 35:05

All right, so hopefully you see the three types of roots, how they’re connected. And I’ve talked a lot about, like building these roots. But the thing is they grow, they change, they wither, they die. And that causes so many frustrations for people. So for example, if we go back to our high school friends here, you know, our soccer practice, geometry friends, at a certain point, you graduate. You’re no longer on the soccer team together, you no longer go to school and sit in geometry class together, maybe we’ll go off to college. And you’ll either develop new ways to stay connected, things to text about, new ways to connect over those specific interests, or you’ll let them die. And letting them die isn’t a bad thing. Like life is changing, we’re not going to be in high school geometry class forever. But that doesn’t mean it’s not sad, when the ways we are connected go away. And when suddenly, you no longer have soccer practice and geometry, even though this might be your best friend in high school by the time you graduate, and you have so many beliefs about them, you know so much about them, you have a ton of emotional intimacy roots, if you don’t find ways to connect, then you aren’t going to update your emotional intimacy and story roots over time.

Alex Alexander 36:38

So if you both go off to college, really don’t talk to each other. You finally meet up four years later after you graduate, you get together, you’re like, “I’ve missed you so much.” Story roots, by the way. Like, I care about you. And so you’re like, I want to do something to show my friend how much I care. So on the way to this dinner, you stop and you pick up chocolate donuts. And you show up and you set them down. Your friend acts kind of weird. And after a while, admits to you that they don’t eat gluten anymore. And seems like silly. But what’s happening here, suddenly you’re like, oh, this person that I say is my best friend that I think knows me better than anyone. But I know them. I apparently don’t know them, because they don’t even like chocolate donuts anymore.

Alex Alexander 37:40

Chocolate donut seems to be their favorite. That is the death of an emotional intimacy roots. We then have to say, okay, that thing I knew about you is now history. That’s fine. You used to like chocolate donuts, what do you like now. But if you’re so caught up on the fact that you don’t know your best friend that well anymore, that’s probably going to get in the way of you staying in the moment and learning new things about this version of your friend. Another example would be when shared experience roots die. So, let’s say that you and a friend used to be the friends that went out every weekend together. After a while, your friend meets someone and has a baby. And they don’t want to go out every weekend anymore. So your options are, you just get together for dinner a couple times a year. There’s nothing wrong with this option, by the way, totally fine option. But it’s gonna feel way different. Because you’re going to sit at dinner probably and you’re just going to tell each other about your life. You’re gonna go through all the recent things that have happened, what’s new, which is really, if you think about it, just both of you reliving your recent past. You’re not making that many memories in the present. So this probably isn’t gonna be that memorable of a dinner.

Alex Alexander 39:09

And you might learn some new details about each other, but you didn’t actually see them. You didn’t witness them. But you heard about them. And there’s something a little different to having a friend tell you that they went and hiked some mountain and actually been with them and hiking the mountain. So you either lean in to just connecting because you care about each other because you’re good friends. Or you find new ways to spend time together. So maybe you used to go out every weekend, but now you’re going to build new shared experience roots because your other ones have died. And you’re going to start doing Sunday movie nights because you can stay at home, the baby can sleep. You’re gonna go on walks with the stroller. You’re gonna join a tennis group. You’ll find new ways to stay connected, make memories be present. Sure, you’re probably going to tell each other about your recent life. But you also are just going to do something together, you’re going to be together, you’re going to make memories together.

Alex Alexander 40:26

And the final one, you know, growing and changing these ones are the story roots. So whatever expectations and beliefs we had, about our best friend in high school, when we said they’re my best friend, the expectation was maybe, you know, like, if I had a bad day, they’d get in their car and come to my house. And now that we’re older, couple decades maybe, we might live across the country, saying they’re my best friend, needs to have a different expectation than they’ll drive over to my house. And sometimes I think that these really big, overarching story roots, these beliefs, like they’re my best friend, what does that even mean? What do you expect from…? Best friend for what? What do you talk about? What do you do together? So, sometimes those story roots needs to die. And I would suggest replacing it with a simpler, more straightforward story root, or a few.

Alex Alexander 41:27

They’re my best friend could be replaced with seven story roots, that’s fine. But they’d be easier like this friend supports my goals, you can set some pretty clear expectations for that. So when I talked earlier about visualizing your friendships as a tree, hopefully you now see that the roots are always growing and changing. And there’s quite a mess of roots down there. And especially when you get to the point of maybe a more present friendship, but a lot of roots of all kinds. Now, some of your simpler friendships are mainly built just on like shared experiences. You don’t have that many details or beliefs about the friendship, but you do stuff together.

Alex Alexander 42:13

Present friendships, kind of got them all. You got a lot of them. And then those historic friendships are mainly held together by your beliefs, your emotional intimacy roots. So your memories, the things you know about each other, big and small intimacies you hold, and you have less of the shared experience roots, which means that you are building less evidence collecting less up to date information to support those story roots. Not a bad thing. But a very important thing to consider when setting your expectations, or if you are frustrated with a friend, asking yourself, are my expectations way too big for how much time we’re spending together? Could I really expect them to know that about me? I haven’t seen them in a year. You know, reworking our story roots also allows us to be on the lookout for really specific evidence that supports our beliefs. It makes us feel connected to each other. And know that we can go to these friends for these certain areas of our life.

PODCAST EPISODE! Hear all about why I created Friendship IRL here.

Alex Alexander 43:28

If you have made it this far into this episode, just wow. Give yourself a pat on the back. This is a lot. And I could talk about this for three more hours. There are so many more examples. But I think that this is a great foundation. It gives you some sense of these concepts and the terms. And my website is full of additional resources on this. I also talk quite a bit about this on social media, both on my Instagram and my TikTok. And I try and point out certain kinds of roots in real life. Because these terms, they’re definitely ones I will use in future podcasts, and writings and discussions. And now that I’ve offered these to you, I hope you’ll start to see them. It’s actually my favorite, because I’ve been using these terms with friends, like in my everyday life for a while now. And I love when a friend will say to me just organically out of nowhere, they’ll say, “Oh well, I realized our shared experience roots died.” And it’s just so heart-warming that my obsessive thinking about this for a couple of years is creating hopefully some language we can use to start to think about how these relationships are actually working in our life and what’s holding them together. And also for us to look at our friendships and consider what actions we might take to reinvest in a friendship, to build a better version, to work through a problem, that we can all start to become our own master gardeners instead of feeling overwhelmed, because we have no clue what’s happening underneath the roots.

Alex Alexander 45:24

And in the end, we can take more intentional action and hit the mark, waste less time, feel less lost, so that we can feel connected to the people around us. I don’t even know how to wrap up this episode. This is just such a pivotal piece. It’s one that I will be talking about forever. So, this won’t be the last episode. And I’d love to chat with you more about this however you choose.

Alex Alexander [45:58]

Thank you for listening to this episode of Friendship IRL. I am so honored to have these conversations with you. But don’t let the chat die here. Send me a voice message. I created a special website just to chat with you. You can find it at alexalex.chat. You can also find me on Instagram. My handle, @itsalexalexander. Or go ahead and leave a review wherever you prefer to listen to podcasts. Now if you want to take this conversation a step further, send this episode to a friend. Tell them you found it interesting. And use what we just talked about as a conversation starter the next time you and your friend hang out. No need for a teary Goodbye. I’ll be back with a new episode next week.